The Draft of Sichuanese Mirror

汉唐宋时,四川依仗山川形胜、远隔王廷,繁育出相对封闭的生态,在政治上甚至享有「不与天下州府同」的特权。蜀中一时人物阜盛,争有「扬一益二」的美誉。然而,蒙元犯境、明末大屠杀喝断了锦城的弱管轻丝,给川峡四路带来了致命打击。「天下未乱蜀先乱,天下已治蜀后治。」——欧阳直在『蜀警录』中记述张献忠乱川时,用此语评判了蜀地的板荡。同样描述蜀地丧乱的还有彭遵泗的『蜀碧』等书——是啊,惨烈的战争揉碎了千百年传承有序的文统、千百载春花秋月的绮梦,所以恨血千年、此地土中犹碧。近现代海洋文明崛起后,蜀地的内陆农耕优势愈发萎缩,终于在历史中逐渐黯淡下去。

During the Han, Tang, and Song dynasties, Sichuan, blessed with its majestic geography and distance from the imperial central court, developed a relatively closed and self-sufficient ecosystem. Politically, it even enjoyed privileges of “being exempt from governance identical to the rest of the empire.” At that time, Shu (Sichuan) was a cradle of flourishing talent, honored with the saying: “Yangzhou ranks first, and Yizhou second (扬一益二).” Yet the Mongol invasion and the massacres at the end of the Ming dynasty violently severed the brocade city of Chengdu, delivering a fatal blow to Sichuan. “When all under heaven is yet to descend into chaos, Sichuan already lies in turmoil; when all is restored to order, Sichuan is the last to heal (天下未乱蜀先乱,天下已治蜀后治).” — In the Shu Jing Lu (Record of Alarms in Sichuan), Ouyang Zhi used this line to describe the upheavals in Sichuan during Zhang Xianzhong’s brutal conquest. Other works, such as Peng Zunsi’s Shu Bi (The Jade of Shu), also described the province’s devastation. Indeed, cruel wars shattered the centries-long literary lineage and poetic dreams, leaving behind blood-drenched earth, where to this day the soil glows faintly green. In modern times, as maritime civilizations rose to dominance, the inland agrarian advantages of Sichuan gradually waned, and the region slowly faded into obscurity within the grand course of history.

庙堂对江湖的提防、权威对史书的专断、富者对卑者的凝视,都使得偏僻的地、偏远的人悄然、赧然。汉唐宋时风流的蜀地,到如今只对更先进者亦步亦趋,对方言鄙弃、对习俗自嘲、对风土解构。有此种种,这里的阳春白雪和下里巴人俱减,既希见严肃典雅的篇章,发展地方文化的体系,也缺乏天然飘逸的涂鸦,抄录坝子上随风摇曳的言子、童谣、经咒、歌哭。

The wary gaze of the central court upon the outlands, the exclusivity of historical narrative by those in power, the condescending stare of the wealthy toward the humble — all have rendered the remote lands and distant people silent and self-effacing. Once so affluent and elegant throughout the old dynasties, Sichuan now only follows more advanced regions step by step, disdaining its own dialects, mocking its own customs, and deconstructing its own cultural identity. With all this, both the lofty and the earthy — the refined classics and the folk ballads — have diminished. There are few remaining solemn and elegant chapters forming a coherent system of local culture; nor is there much of that natural, effortless graffiti that once transcribed the wind-blown sayings, lullabies, mantras, and cries sung across the open plains.

所以我拍下这些碎片,写下这些隙笔,汇成『蜀鉴』的底稿。这一摞『蜀鉴稿』偶尔凭古、偶尔寻仙,但种种跨越时空的闲章,都描摹着蜀地的今日、蜀人的今世,作为失声于当代的僻土的见证,愿为他日阳春白雪、下里巴人的伏笔。

And so I captured these fragments, penned these marginal notes, to form the groundwork of Shujian (蜀鉴). This Draft of Sichuanese Mirror (蜀鉴稿) invokes the ancients, seeks the immortals — but each of these idle marks that bridge time and space seeks to portray the Sichuan of today, and the Sichuanese of this era. As a testimony from this silenced land in the contemporary age, may it serve as a prelude — whether to elegant arias or rustic ballads — for a spring yet to come.

Wondrous Figures – Mount Doutuan, Jiangyou

“Willing to follow Ziming, refining fire and forging elixirs of immortality.”

从成都东到江油的高铁,在淡蓝色的七月天空下,穿过川北连绵的绿野。即使是最晴朗的季节,四川的天空也不尽兴——记忆中大学时,在北京的郊区,一抬头,就被蓝得发黑的宇宙吸走了魂,若有所失;端午水过后,浓积云卷过贵阳花溪的山脊,镶成湛蓝穹窿的花边;川北秀丽的丘陵、艳绿的田地、蛇行的林线高头,却只覆盖着淡青、淡蓝的天幕,几阵、几脉、几绺的云,正是现在我透过高铁车窗看到的景象。

The high-speed train from Chengdu to Jiangyou slices through the endless green fields of northern Sichuan beneath a pale-blue sky of July. Even in the clearest season, Sichuan’s sky seems reluctant to unveil itself. I recall my university years in the outskirts of Beijing—look up, and the dark blue of the cosmos seemed to draw the soul away, leaving a trace of emptiness. After the Duanwu (mid-May) rains, cumulus clouds rolled over the ridges of Guiyang, trimming the azure dome with a frilly edge. But the elegant hills of northern Sichuan, vibrant green fields, and serpentine forest lines rise toward a canopy of pale cyan and sky blue. Flecks and wisps of cloud now drift across the view outside the train window.

从江油站出发的车子,钻进乡、场、坝,贴着涪江,沿着树阵滑行。在树阵和车窗缘勾勒的画框深处,窦圌山一会侧身骨立、一会迎面而来。

Departing from Jiangyou station, our car winds through villages and markets, tracing the banks of the Fu River, gliding beside rows of trees. Framed by roadside forest and the edge of the window, Mount Doutuan appears—turning sideways like a bony sentinel, or facing us head-on.

盆地西北部的江油,枕带涪江,土地平旷。江油的名人们,谪仙李白、真仙哪吒、佛法与武艺并重的海灯法师,都萦绕着仙气与侠气。不独江油,蜀地千里,多有这种气象。市镇经济、王化边陲、佛道信仰、袍哥会……更重要的,是在峻险的鸟道尽头、重隔的巴山脉尾,这个孤僻的盆子里头,江山自是旖旎,又常披云带雨,织染了幽朴、清逸的基色,成就了仙人、侠客、种种非常奇士的思想、表达、骄傲、抱负。

In the northwestern corner of the Sichuan Basin, Jiangyou lies flat and open, cradled by the Fu River. The famed figures of Jiangyou—Li Bai, the “banished immortal”; Nezha, the true immortal; Master Haideng, adept in both Buddhist doctrine and martial arts—all seem touched by the airs of mysticism and chivalry. Not just Jiangyou, but much of Sichuan teems with this unique temperament. Markets and guilds, the fringe of imperial governance, the blend of Buddhist and Daoist faiths, the Brotherhood of Paoge-hui—all flourish here. More crucially, tucked away at the terminus of treacherous mountain paths and the tail end of the Bashan ranges, this secluded basin is draped in rain and cloud, dyed in tones of quiet rusticity and serene elegance. Here, the very landscape breeds extraordinary minds—immortals, knights-errant, and wondrous souls with unconventional expressions, pride, and aspirations.

午饭吃到了牛肉粉和绿豆凉皮。与川南相比,川北不太嗜辣,但不管是哪里,都酷爱用红油——筷子伸进红色沼泽中,翻出一块肉,肉的纹理上还流淌着鲜红的油汁。牛肉粉口感不错,但绵阳和南充两个川北邻居之间素有谁家米粉更好吃之争,作为南充人,必须自豪地说一句,还是南充粉好吃:)

Lunch was a bowl of beef rice noodles and chilled mung bean jelly. Compared with southern Sichuan, the north is less enamored with spice, though red chili oil remains a regional obsession. One dips chopsticks into a red slick, fishing out a piece of meat still glistening with crimson juice. The beef noodles were quite good, though a friendly rivalry persists between Mianyang and Nanchong—neighboring cities—over who makes the better noodles. As a Nanchong native, I must proudly declare: Nanchong wins 🙂

敦实的基座上,几株孤峰攒在一起,壁立千仞。峰崖光滑,峰顶却长满了树,各自环抱着一座庙宇。我们只能爬到玉皇殿所在的峰顶,另一峰的庙宇和这边的崖壁由铁索相连,再一峰的庙宇又由铁索和第二峰相连。想要从玉皇殿朝觐对面两峰,只能踩铁索渡崖而去。老照片里,还能看到过去的僧人抓一条铁索,踩一条铁索,从容往来几峰之间。现在每天都有专人定时免费表演渡崖。我们凑巧看到了中午一点半的一场,只见烈日之下,红衣大爷手脚并用,在铁索上时而徐步,时而张臂如鹤,时而倒挂如猿。他猩红的身影,透过背后的两道绝壁,投在一线之外的青天、碧野之中。等到了对面庙宇,他翻进阁楼,敲钟礼神毕,又翻出到瓦檐上,炫耀着做起气功。

Rising from a sturdy base, several jagged peaks cluster together in sheer verticality. The cliffs are smooth, yet their summits burst with trees, each embracing a temple of its own. We managed to climb only as far as the Yuhuang-dian (Jade Emperor Temple). The temple on the neighboring peak is linked to this one by iron chains, and the third by another set. To pay homage across the ravines, one must tread these iron bridges. In old photos, monks can be seen grasping one chain, treading another, crossing effortlessly between the peaks. Today, performers traverse the cliffs daily, free of charge. We happened upon a 1:30 p.m. show: beneath the blazing sun, a red-clad master moved across the chains—sometimes striding slowly, sometimes posing like a crane, sometimes hanging upside down like a gibbon. His scarlet silhouette, framed by twin vertical cliffs, projected onto the verdant land and sky beyond. Reaching the far temple, he clambered into the pavilion, struck the bell in reverence, and then reappeared on the rooftop, displaying qigong moves.

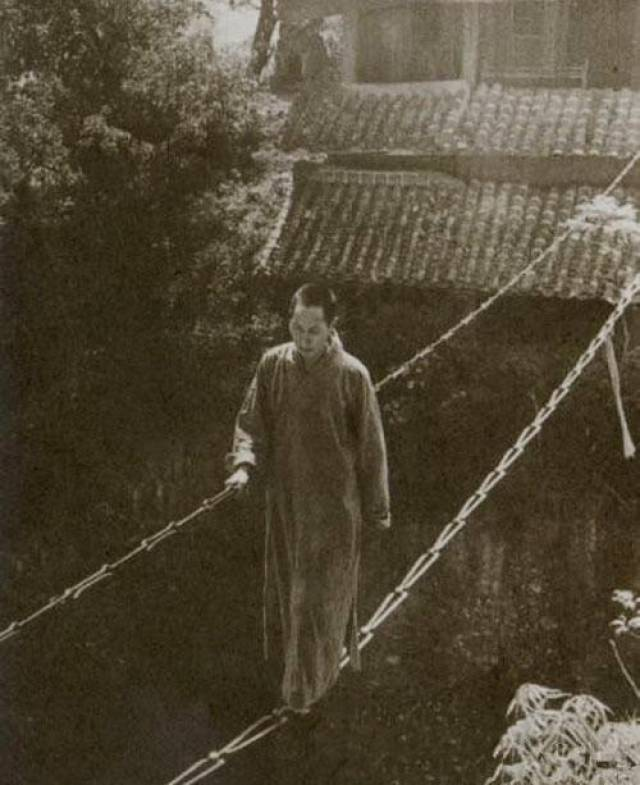

大爷已经70多岁,每天和别人交替演出,伟哥询问才得知,他一月休四天,薪酬堪温饱,家在射洪,9岁就来圌山,学艺数秋,80年代景点商业化之初,等客人点了才出演,现在变成了每日多场按时活动。来来往往,已经在铁索上走过二三十个年头,现在还在教徒弟(视频介绍)。

The master, over 70 years old, alternates performances with others. Wei-ge (my companion) asked and learned that he works all but four days a month, earning just enough to get by. A native of Shehong, he came to Mount Doutuan at 9 and had studied acrobatics for years since then. In the 1980s, when the site first became commercialized, he performed only upon request. Now, it’s a scheduled daily routine. He has crossed the iron chains tens of thousands of times and is now still active training apprentices (see video).

几寻山路过后,突然走到了两峰之间的坑底。从坑底仰望艳阳中那一丝恍惚的铁索,心里再次感叹:数十年不辍,每日多场,想必大爷已经看腻了坑底这些花花草草,却也为不掉进这花花草草谨慎了数千万次。而我们这些来了便去的过客,啥时候还能看到这种不要钱的生猛奇艺……

After a few more turns along the mountain path, we suddenly found ourselves at the base of the ravine between two peaks. Looking up at the trembling wire under the blazing sun, I couldn’t help but marvel again: after decades of daily walks across, surely the elder has long grown weary of the flowers and grasses at the ravine floor—yet he must have glanced at them tens of millions of times, cautious with every step to not fall. And we, mere passersby, when might we ever again witness such a raw, uncommodified spectacle?

崖底山路上还会路过5.12的巨大坠石。临近北川的江油那时遭难严重,窦圌山的云岩寺坍塌大半。

The path below the cliff also passes by a massive boulder dislodged during the May 12 earthquake. Jiangyou, near the epicenter, was severely hit—half of Cloud Rock Temple on Mount Doutuan collapsed.

The Borderland of Han – Bao’en Temple, Pingwu

“By this merit may I adorn the Pure Lands of the Buddha; to repay the fourfold grace above, and relieve the threefold suffering below.”

下窦圌山时刚过中午,于是临时决定赶去平武,看完报恩寺,当晚就可以回到江油。一路上车从平坝穿进深山,地形陡变,我们已经走到四川盆地的边缘。从江油到平武途经北川境内,这一带是当年地震的极重灾区。包车的师傅说,江油在震中遇难几百人,多是被房顶矮墙坠落砸死,隔壁的北川更不必说。他的堂弟也是在山谷中游玩时被巨石击中——即使同经历5.12,但听闻核心区灾民的讲述,仍感到生死迫近、虽真如幻,横生无限感慨。

It was just past noon when we descended from Mount Doutuan, and on a sudden impulse, we decided to press on to Pingwu to visit Bao’en Temple, planning to return to Jiangyou the same evening. Our car left the flatlands and began its climb into the mountains, the terrain shifting dramatically—we were approaching the edge of the Sichuan Basin.

The journey from Jiangyou to Pingwu passes through the borders of Beichuan, one of the areas worst hit by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Our driver told us that several hundred people died in Jiangyou alone, most crushed beneath collapsing roofs and low walls. As for neighboring Beichuan—there was hardly need to say more. His own cousin had been struck by a boulder while traveling in a mountain valley. Even having experienced that earthquake myself, hearing firsthand the stories from survivors of the quake’s epicenter made death feel palpably near—so real it bordered on illusion—and filled me with boundless sorrow.

弯弯绕绕的路着实费时,到平武县城时报恩寺已经关门。执念所在不忍直接返程,我当即订下寺前酒店,放伟哥一人回去。平武再向北就到了青川、九寨沟、甘肃陇南,这一片处在多民族地区,饮食也从典型川菜向西北口味过渡。在清真馆子吃完粉蒸牛肉,沿着奔腾的涪江散步片刻。多数四川城市都有一条滨江路——苍溪、阆中、我的故乡南部,由北而南襟带嘉陵江,而平武、江油、绵阳人则吃着涪江水长大。从成都过绵阳、到广元、闯剑阁、入汉中,这条蜀道运送了秦蜀、陇蜀的物资和消息,反过来从剑门到剑南,一路上又听闻了不韦、玄宗、僖宗、拾遗、放翁、迁客骚人的夜雨霖铃。

The winding road consumed more time than expected. By the time we reached Pingwu, Bao’en Temple had already closed its gates. Reluctant to turn back, I booked a hotel directly across from the temple, letting Wei-ge return alone. North of Pingwu lie Qingchuan, Jiuzhaigou, and Longnan in Gansu—a region inhabited by diverse ethnic groups, where the cuisine begins to shift from Sichuan flavors to the bolder tastes of the Northwest. I had a dinner of steamed beef with rice flour at a halal restaurant, then took a short walk along the rushing Fu River. Most cities in Sichuan have a riverside road—Cangxi, Langzhong, and my hometown Nanbu all lie beside the Jialing River from north to south, while people of Pingwu, Jiangyou, and Mianyang drink from the waters of the Fu. From Chengdu through Mianyang to Guangyuan, past Jianmen Pass into Hanzhong, this was once the ancient Shu Road, a vital artery for goods and messages between Qin and Shu, Longxi and Sichuan. And flowing back the other way, from Jianmen to Jiannan, came the echoes of Lyu Buwei, Emperor Xuanzong, Emperor Xizong, neglected scholars, poets in exile—stories carried in the sound of rain and wind at night.

次日清早,平武一改前日的艳阳高照,远近的青山都掩映在凉雾中。报恩寺的山门前人迹寥寥,我又庆幸获得了清静的一日。敕修报恩寺由土司王玺及其子建于正统天顺年间,以报皇恩,是国内少有的明前期完整寺院。在全国文保的名头之下,报恩寺也属于清华建筑学院的研究基地,对此衷心感到有缘(实际体感全国范围内的高规格官式建筑都与清华有缘……)。

The next morning, the dazzling sunlight of the previous day had given way to a cool mist that shrouded the green hills near and far. At the temple’s main gate, there were hardly any visitors. I felt fortunate once again to be gifted a day of tranquility. Bao’en Temple was commissioned by the local chieftain Wang Xi and his son during the Zhengtong and Tianshun reigns of the Ming dynasty, built as an act of gratitude to the emperor’s grace. It is one of the few surviving temple complexes from the early Ming period. As a nationally protected heritage site, Bao’en Temple also serves as a research base for the Tsinghua School of Architecture—a delightful coincidence, though I’ve come to realize that most high-status official buildings across the country seem somehow tied to Tsinghua…

寺院的官式风格明显,歇山顶、绿琉璃瓦、藻绣平闇、阔笔榜书,线条平正,与飞檐俏丽、骨骼灵秀的窦圌山云岩寺等蜀地民间建筑迥异,反倒遥遥呼应曾拜访过的北方精品——蓟县独乐寺观音阁、大同华严寺和善化寺。

The temple’s official architectural style is evident: hip-and-gable roofs, green-glazed tiles, painted beams, flat plaque calligraphy in broad strokes—all balanced, upright lines. This style differs starkly from the elegant, spontaneous beauty of folk structures like Cloud Rock Temple on Mount Douzhui. Instead, it echoes the refined northern masterpieces I’ve visited—such as the Guanyin Pavilion at Dule Temple in Jixian, the Huayan Temple and Shanhua Temple in Datong.

匆匆看完报恩寺,还没到十点钟,于是又匆匆打车回江油、下成都,折向西南下一程。车窗外高岭深谷、涪江迤逦,但远山长、云山乱、晓山青。

Having explored the entire complex in haste, I found it was not yet 10 a.m.. So I quickly hailed a car back to Jiangyou and returned to Chengdu, veering southwest for the next stage of the journey. Outside the train window, high ridges and deep valleys passed by, the Fu River winding along—distant mountains long, cloud mountains chaotic, morning hills a fading green.

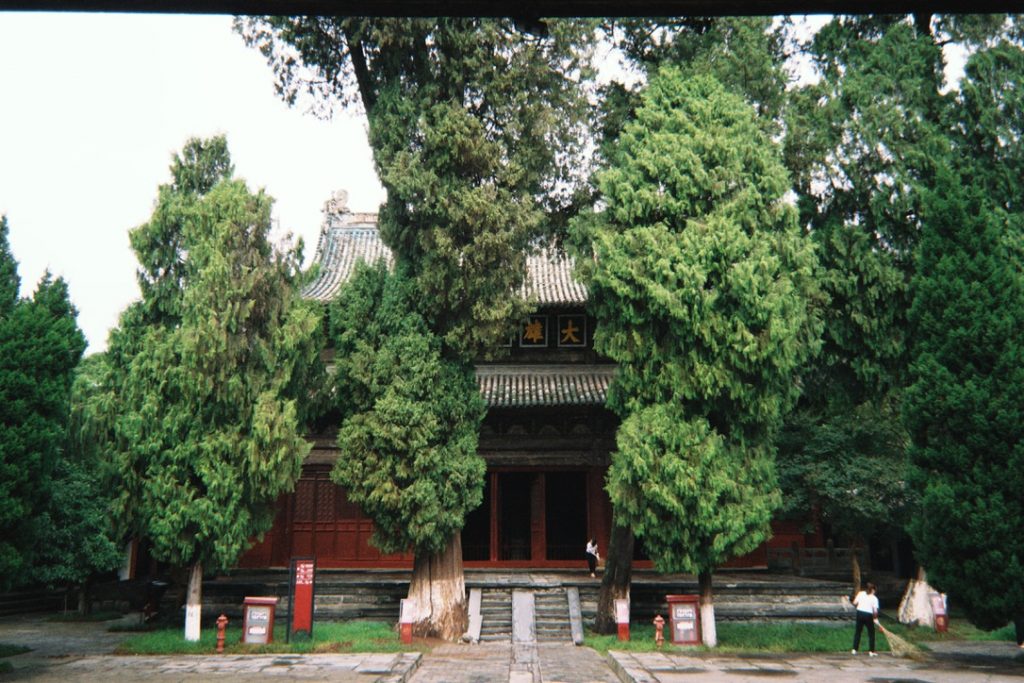

Immortal Affinity – Mount Qingcheng, Guan County

“As a guest of Qingcheng, I do not spit upon its soil. For I cherish Zhangren mountain, where vermilion steps lead into mystic depths.”

我深感「幽」是蜀韵之钟粹,而青城山正是幽意之祖脉。

I am deeply convinced that you (serenity) is the purest distillation of Sichuan’s temperament, and that Mount Qingcheng is the very ancestral vein of this you-ness (幽; mystery, tranquility, seclusion).

从青城山站到前山侧峰脚下的车程只需10多分钟,但从山脚到玉清宫的路就很折磨人了。背着石头一样的相机包迈开步子,裹着向晚的余热,踏着湿滑的石阶,趟过混合泥土的涧水,一路上走走停停,好几次听到重重的心跳,不禁纳闷宫中的道众难道出行也得走这荒僻的山路,喘气如牛?望着绵延的阶梯,苦算着玉清宫到底在何处时,一道朱漆的廊檐、茶园的矮树终于从树丛中探出了头。从山脚爬到玉清宫门前,用了将近半个小时,为了借宿一晚,汗水不知湿透了几次短袖。

The drive from Qingchengshan railway station to the foot of a side peak on the Front Mountain takes just over 10 minutes. Yet the journey from the base to the Yuqing Palace is an entirely different ordeal. Laden with a camera bag heavy as stone, I trudged forward in the lingering heat of dusk, stepping carefully over slippery mossy stairs and shallow muddy streams. I paused and restarted again and again, heart pounding heavily in my ears. I couldn’t help but wonder—do the Daoist adepts of the palace also have to traverse such desolate paths every time they leave the mountain? Do they, too, pant like oxen on these endless stairs? Just as I was calculating how far the palace might still be, a vermilion eave and low tea shrubs peeked out from the forest above. It took nearly half an hour to ascend from the foot of the mountain to the entrance of the Yuqing Palace. I was already drenched in sweat many times over in hopes of lodging there for the night.

年轻的道长带我入住后,便简单逛了一遍观内。与川内大多数寺观一样,玉清宫利用山地形势,一进院落一个高台,从山门走到最后的三清殿,总共三层标高,每进院落都围绕天井,庭中苔痕上阶绿,满目阴翳。伟哥先我半天到青城山,已从前山下至宫中,与我会合于饭堂中,此时已近日暮。饭堂的敞廊朝东张开,极目远望,都江堰市区乃至更远的成都似乎都敛入群青色的地平线。

After checking me in, the young Daoist priest gave me a brief tour of the temple. Like many monastic complexes in Sichuan, the palace is built in accordance with the mountainous topography. Each courtyard sits on its own elevated platform. From the Shanmen gate to the final Sanqing Hall, there are three terraced levels in total. Each courtyard is centered around an impluvium, with its inner yard dappled with moss and steps tinged green with shadow. Wei-ge had arrived at Mount Qingcheng half a day earlier and descended from the Front Mountain to meet me at the palace. We reunited in the refectory just before nightfall. The open corridor of the refectory faced eastward, offering a panoramic view: in the far distance, the cityscape of Dujiangyan (Guanxian)—and even Chengdu—seemed to gather along the indigo horizon.

在还没点灯的廊下稍坐片刻,乌云渐渐从背后的山头翻过来,雨点眨眼间铺满了院落。遥远的空中雷声隐隐,神明似乎为我们的徒步拜访赐雨洗尘。

As we sat quietly in the still-unlit corridor, dark clouds spilled over the peaks behind, and within moments, raindrops blanketed the courtyard. Thunder rumbled faintly in the heavens far above, as if the gods were bestowing a rain to cleanse the dust of our pilgrimage.

晚饭有南瓜汤、烧椒皮蛋、土豆,听说今天的午饭是烧鸡,才反应过来,道观的饮食戒律和佛寺不同。过去在禅林五观堂中吃过的斋饭,都将素菜做出了最可口的味道——当然,这种清淡的美味,一大半归功于跋山涉水、朝觐神佛的劳累。

Dinner was pumpkin soup, stir-fried chili with century eggs, and potatoes. The lunch had included roast chicken—only then did I realize that the dietary restrictions of Daoist palaces differ from those of Buddhist temples. In the past, I had tasted vegetarian meals at Chan (Zen) monasteries’ “Wuguan (Five Contemplation) Halls,” where plain dishes were elevated into exquisite flavors. Of course, such light and pure deliciousness owes much to the exhaustion that comes from mountain treks and devotional climbs.

Majestic Deeds – Dujiangyan

“Dig the deep channel, build the low weir.”

“Spring hues of the Jin River embrace all under heaven. The floating clouds over Yulei change with the ages.”

Craftsmanship – Ming Shu Kings’ Tombs, Yongling, Anyue and Dazu Rock Carvings

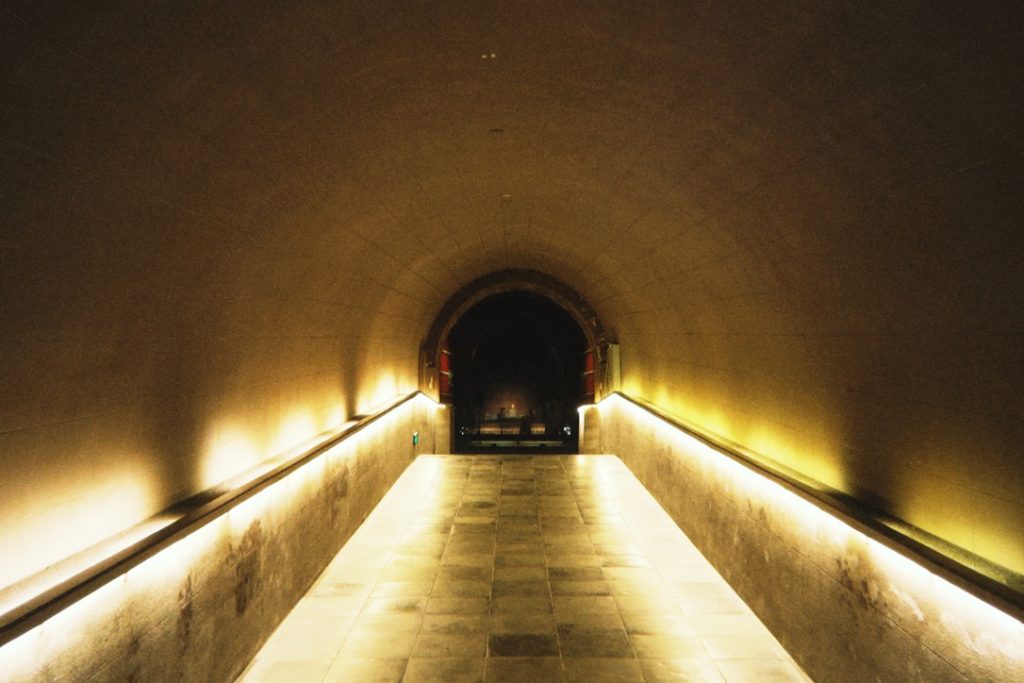

原位于天府广场的蜀王府已荡然无存,如今只能凭借照片揣摩王宫的旧影。明蜀王陵的地宫仿照王府而建,由阴而阳,为今人提供了想象的空间。

The original Shu King’s Palace once stood proudly at today’s Tianfu Square, but now has vanished without leaving a trace. All that remains are old photographs, by which one might imagine its former magnifence. The subterranean tomb of the Shu Kings of Ming was modeled after the palace above—projecting yang to yin—and thus offers modern visitors a passageway for the imagination.

前蜀王建的永陵地宫和两蜀文物布展意外地精致,想了想正是五代这个被历史书忽略的「乱世」最关键,承唐启宋,开辟了蜀地最风雅阜盛的纪元,赢得「扬一益二」的美誉。小时候背东坡词,印象深刻的就是洞仙歌的起首,写尽摩诃池上蜀主的风流:『冰肌玉骨,自清凉无汗,水殿风来暗香满。』清凉的夜色简直太治愈成都的暴热……

The subterranean palace of Wang Jian, founder of Former Shu, along with the artifact exhibition from both Former and Later Shu dynasties, turned out to be unexpectedly decent. Upon reflection, it is precisely the period of Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms—often dismissed by historical textbooks as mere “chaos”—that constructs a pivotal bridge between the affluence of Tang and Song. This so-called turbulent era opened a flourishing, refined chapter in Sichuan’s cultural history, one that earned it the praise: “Yangzhou ranks first, and Yizhou second.”

One of the most vivid passages I memorized as a child from Su Shi’s poetry was the opening of Dongxian-ge, which captured the romantic air of the Shu monarchs by the Mohe Pool:

“Skin of ice, bones of jade,

From coolness born, untouched by sweat;

The scent of breeze in water halls drifts gently, unseen.”

我们常常好奇历代皇宫的模样,努力复原阿房宫、未央宫、大明宫的雄姿。对于规模稍杀的王宫,人们的兴趣就没那么大了。

We often marvel at the imperial palaces of dynasties past, striving to reconstruct the grandeur of Epang Palace, Weiyang Palace, or Daming Palace. But when it comes to smaller-scale kingly palaces, public curiosity tends to falter.

我对王府建筑的兴趣来源于『聊斋志异・巩仙』的阅读记忆。巩仙人运作仙法,自由出入于鲁王宫禁,戏弄中贵、取悦鲁王、张开袖中乾坤成全伉俪姻缘。文中,巩仙买通中贵,游览王府后苑一段尤为新鲜:

至无人处,道人(巩仙)笑出黄金二百两,烦逐者(门卫)覆中贵(即宦官):「为言我亦不要见王;但闻后苑花木楼台,极人间佳胜,若能导我一游,生平足矣。」又以白金赂逐者。其人喜,反命。中贵亦喜,引道人自后宰门入,诸景俱历。又从登楼上。中贵方凭窗,道人一推,但觉身堕楼外,有细葛绷腰,悬于空际;下视,则高深晕目,葛隐隐作断声。惧极,大号。无何,数监至,骇极。见其去地绝远,登楼共视,则葛端系棂上;欲解援之,则葛细不堪用力。遍索道人,已杳矣。束手无计,奏之鲁王。王诣视,大奇之。命楼下藉茅铺絮,将因而断之。甫毕,葛崩然自绝,去地乃不咫耳。相与失笑。

一个仙法作弄的片段,于亦真亦幻中侧写王府宫室靡丽,权威中不失诙谐、怪诞,不同于完全森严刻板的皇宫。

My own interest in kingly architecture was sparked by a memory of reading Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, specifically the story of Gong Xian. Possessing supernatural powers, Gong Xian moved barrier-free through the forbidden grounds of the Lu King’s palace, teasing eunuchs, amusing the king, and conjuring up heavenly marriages from the universe within his sleeve. One episode where he bribes a eunuch to tour the king’s garden struck me as particularly vivid:“At a secluded corner, the Daoist (Gong Xian) smiled and drew forth two hundred taels of gold, pleading with the eunuch: ‘I have no desire to see the prince, but I have heard that the rear garden—its blossoms, pavilions, and terraces—is a matchless wonder in the human world. If you could guide me on a stroll, I could die content.’

At a secluded corner, the Daoist (Gong Xian) smiled and drew forth two hundred taels of gold, pleading with the guard: ‘I have no desire to see the king, but I have heard that the rear garden—its blossoms, pavilions, and terraces—is a matchless wonder in the human world. If you could guide me on a stroll, I could die content.’

The guard was delighted and conveyed the request. The eunuch too was pleased and led the Daoist in through the back gate. They toured all the sights, then ascended a tower. As the eunuch leaned against the window, the Daoist gave a sudden push. The eunuch fell—suspended in mid-air by a fine hempen cord looped around his waist. Gazing downward, he saw only dizzying depths. The cord creaked ominously as if ready to snap. Terrified, he screamed. Soon attendants arrived, equally aghast. From below he hung impossibly high; from above they saw the cord tied to a railing, too thin to bear their strength. The Daoist was nowhere to be found.

Having no solution, they reported to the king. The king came and marveled in astonishment. Mats and bedding were laid below, and just as all was ready, the cord suddenly broke on its own—yet he landed safely, from barely a foot above ground. All present burst into incredulous laughter.”

Through this prank—half real, half magical—we glimpse not only the sumptuousness of palace interiors but also a tone of whimsy and strangeness that sets them apart from the solemn rigidity of imperial precincts.

匠人的角色是否被我们低估了?在古代,匠人的技艺是师承的、作坊式的,他们的营造规矩、审美观念来自上一代,再加入一部分个人的情趣。匠作师承和作坊经办都受交通所限,仅在局部地区活动,所以当地的工艺品极大程度上受到当地匠人系统的支配。由此而言,本土的风格和意蕴,乃至基于形而下的器物所生发的形而上的思想,都奠基于这些不太起眼的匠人手上。

Have we underestimated the role of craftsmen? In ancient times, a craftsman’s skill was passed down through apprenticeships and workshop traditions. Their codes of construction and aesthetic sensibilities came from prior generations, mixed with a trace of personal predilections. Because these workshops operated within limited regions—bound by the constraints of geography—their techniques and styles were deeply local. Thus, the visual language, symbolic meanings, and even the metaphysical ideals embedded in physical forms were, to a great extent, born from the hands of unassuming artisans.

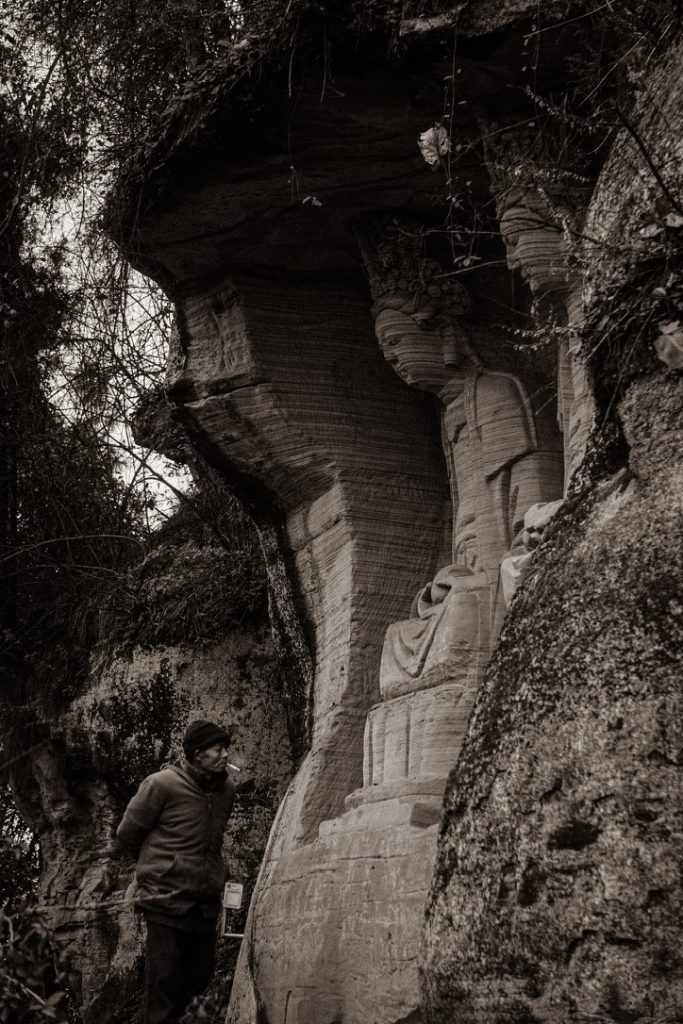

所以,当比对蜀僖王陵中细密的石刻飞檐翘角和明定陵光洁的地宫内室,在刨除礼制和代差因素后,我仍隐约感到蜀地和京师的匠作工艺之别;当比对大足石刻和安岳石刻时,我也微觉:即使同处川东,同气连枝,都有「灵秀」的地方韵味,大足的匠作似乎更与富绅、大寺有密切联系,遗迹簇聚、造像豪迈,有集大、唱晚的晌午、日暮气象,而安岳匠作散见于乡野禅林,如星星之火,造像从朴拙到精细,掩映着草创、试错、归纳的轨迹,正经历着技艺的晨曦。

As a result, when comparing the intricate carved eaves of the Ming Shu tombs with the polished interiors of the Ming imperial mausoleum (Dingling), one senses that, beyond ritual norms and dynastic gaps, a difference in craftsmanship between Shu and the Capital Beijing. Similarly, when contrasting the rock carvings of Dazu and Anyue, though both in eastern Shu and closely related in spirit, one still perceives subtle distinctions.

Dazu’s carvings seem more closely linked to elite patrons and major temples. They are clustered, majestic, and assertive—like the grandeur of midday or twilight, vast, conclusive and sonorous. Anyue’s carvings, on the other hand, are scattered among countryside temples and forest shrines. The sculptures range from rough to refined, revealing a trajectory of experimentation and evolution—evidence of a craft still in its dawn.

只是匠人们处在四民的边缘,不能像士人一样书刻岁月的史书,因此每当我们考察风土的根源,都习惯性地归功于能说话的「士」,欣赏他们的德、功、言、审美观念。

But craftsmen, situated at the margins of the social order (literati, peasant, craftsman, merchant), left behind no chronicles as scholars did. Thus when we investigate the roots of regional culture, we reflexively credit the shi (士) class—the literati—with its virtues, achievements, philosophies, and aesthetics.

The Draft of Sichuanese Mirror