Living Lives, Dying Lives

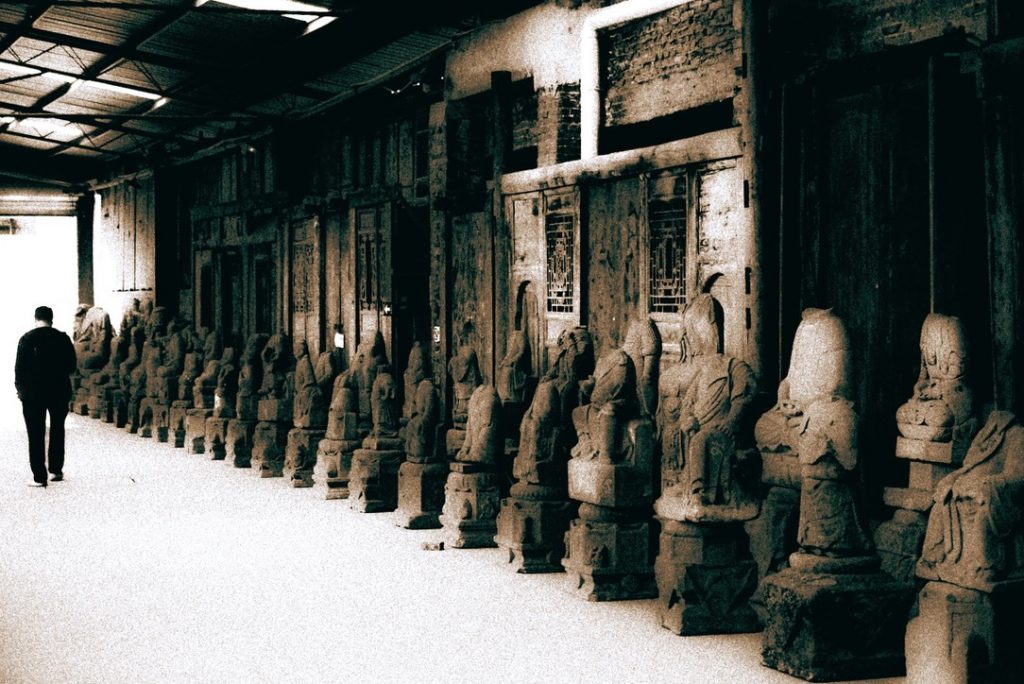

傳統的意義還能如何以具身的體認啓發當下人,令你我他主動以憐惜與尊崇的態度誠摯挽回文脈的陵夷?對我而言,現今就是最佳的機會。七月十三和十四分別是貴州和四川的七月半,挨家挨戶於日落後蹲在路邊給祖先燒紙。從前農村人直接在院壩或墳前堆柴,而今的城裡人卻要冒著「創衛」運動之大不韙,偷偷在小區花壇邊、停車場外插香燃蠟,輕輕熰起一炷青煙,在幽藍的夜色中遙祭鄉壙的祖靈。

How could tradition edify people today, in an embodied way, to penitently and respectfully retrieve the decaying orthodoxy? For me, now is the perfect time. The Mid-July (七月半) falls on 13 and 14 of lunar July for Guizhou and Sichuan separately, when households burn paper money along the streets for their own ancestors. In the past times, village people could pile up firewood straight in their farmyards or in front of the tombs, while city residents nowadays, at risk of infringing the “sanitation-making” policy, ignite incenses and candles furtively by the community flower bed and parking lots, softly offering the smoke wisps in the indigo of the night to their far-parted ancestral spirits in hometowns.

和別地不同,我的老家四川七月半化紙,需要將錢紙裝進一種信封般的白色袋子中,方言稱作「fuzi」。原先,我以為漢文就是「福紙」,但午飯間問過民族學專業的父親,才知道竟是「袱子」這等古雅的名諱。

Unlike the practices in other places, Mid-July paper-burning in my hometown, Sichuan, features the use of an envelope-like packet containing paper money, which is called “fuzi” in our dialect. I’d thought it should be written as “福纸”, symbolizing ancestor-blessed fortunes to the offspring, but a lunch chat with my father, who’s a rather informed anthropologist, corrected me with its real name “袱子”, an unbelievably antediluvian yet straightforward appellation for parcels or packages.

沈沈午覺醒來,惺忪地坐在桌前,看著家人在袱子上為十六年前離世的外祖父、去年新故的外祖母、連我媽也未曾謀面的諸外祖一一添上考妣的尊號,此情此景難免五味雜陳,引我憶起去年此時坐在茶園敞廊下,一邊向身旁的外祖母詢問家族亡人名諱,一邊代筆寫袱子的舊事。不同的唯有二十年來養育恩重的婆婆,淹滅了昨昔案畔的慈容,空餘下眼前的一撇與一捺。母親說,外祖父母在生時,曾憂慮身後哪還有子女年年飄墳掛紙;母親也在二老合葬的新冢前嘆息:「親恩三代而斬,再往後還有誰想起祖地的墓塋?」

Waking up from a deep nap, I came to grab a chair and sat blearily at the table, watching my family writing down the deferential titles one by one for my grandfather who passed away 16 years ago, my grandmother who just departed this life last year, and all those late grand-grandparents who my mother had even no chance to see. Touched by this emotionally mixed scene, I couldn’t help but start recalling me sitting out in the porch at this exact time last year, asking grandma aside for the names of my deceased ancestors, and penning them down on fuzis. The only difference from then was that my grandma, to whom I had owed 20 years of debt for bringing me up, had gone with her amiable countenance, leaving me the mere strokes on the fuzi patching vainly together a name. “While your grandma and grandpa were alive,” my mother said, “they wondered if there’d be any children who still remember to visit their tombs after their death.” Standing by my grandparents’ graves, my mom sighed again, “The bonds break up just after three generations, and then who knows the graveyard our ancestors rest in?”

中元日近,我和母親夜夜的夢里,都還是婆婆的靈識,絮說著逾越生關死劫的眷念。在每包袱子沿上塗好膠水、間或停下的母親說:「過去這些事都讓你姨媽代勞,今年你婆走了,我才真想起該自己燒。」剛說完又懷疑起我爹在袱皮上寫的「郵寄」格式不妥。接著話父親又對我自負起來:「你們總還不信專業人士,況且這是我們秀才先人傳下的寫法。你爺爺以前嫌我字不好,要看秀才先人的袱子方稱板正。」待把四十封袱子收拾歸一,只等日落後借火的秘力變化陰陽了。

As Mid-July approached, both mom and I, in our nightly dreams, listened to my grandma mumbling about our affinity that transcended the barriers of life and calamities of death. In the break after applying glue to the edge of each fuzi, mom said, “Your auntie used to do all the stuff before grandma left us, but this year I just came to realize we should get this done ourselves.” Just as the recollection finished, she right away started to doubt the form of address that my dad had put on the fuzis. Soon her challenge was countered by dad’s boast, “So hilarious of you to distrust an expert! Not to mention this is even what our ancestor the Xiucai (a scholar passing the official entry examination in ancient China) had passed down. Your grandpa ever teased me about my sloppy handwriting — should really know how elegantly Xiucai had written!” Having finished all the 40 fuzis, all we needed to do then was convert them after sunset, by the occult might of fire, from “yang” to “yin”.

飯後散步時,母親說:「你婆以前言子‘七月半是真的,過年是興的’——換言之,年前燒紙是世人的習俗,而七月半才是故人真收錢的日子。」這兩晚的臥室里,樓下化錢的氣味揮之不去。黢黑的窗外、迷蒙的青煙,抹糊了視線,卻清楚地呼喚著與煙有關的回憶。外祖父下葬的拂曉,墓穴旁蹲著嗩吶隊,嗩吶隊背後的青松梢上,羸弱地纏繞著線圈一樣的煙。去年底匆匆離校回老家趕上外祖母畢七,看著累累的柴枝上熰起的草煙,和我圍著墓冢插滿一圈的香燭上升起的煙融在一處。臘月將盡,給先人們蒸好整隻雞,在餐桌腳不遠處燃起香煙,惘然地呼喚杳無蹤跡的、深愛的、永難追悔的名相:伏惟啊,尚饗!周禮以降,燔柴祝文,一柱煙,上達青天,拜天官,下賜福德。肉體凡胎,眾生飛不到南天的帝閽,只好以柔韌的香煙,登高自卑,將訴不盡的心事說向神聽。

On the walk after dinner, mom said, “Your grandma had told us that Mid-July is real while the New Year should just be a fad — in other words, it’s only an unfounded custom to burn paper toward the New Year, but on Mid-July the deceased will truly collect their money from this world.” Over these very days, my room has been awash with a strong smell of burning from out in the community garden. Outside the window, far into the darkness, the bluish smokes blurred my sight but clearly woke up my smoky memories. At the dawn of grandpa’s burial, the grave was guarded by a suona band squatting beside, behind which high above the pine twig was draping feebly a loop of smoke. Toward the end of last year when I rushed to my hometown for grandma’s Biqi (the seventh and final Qi, which is ritually done every seven days after a person’s death), the grass smoke rising from heaps of firewood blended with that from the incenses and candles I lit up around her rest place. As lunar December came to an end, we steamed a whole chicken for the ancestors, burned the incense on the ground by a table leg, and called almost in vain upon the disembodied, beloved, yet irretrievable names, “May you take all these offerings!” Since the immemorial establishment of the rites, we the people have learned to burn wood, recite incantations over liturgy, and rise a puff of smoke high up to the ether, in the hope of receiving divine blessings. Caged in mortal flesh, we couldn’t fly to the portal of the heavenly palace — the endless thoughts could only rest on a slim wisp of smoke, channeled from the very bottom of the mundane world up to the sacred top where gods reside.

最看重儀禮的一代人真切地凋零了。從前世世代代庭訓傳授的慎終追遠,我似已無信心能於我這一代、乃至下一代仍葆生氣。在青青杏壇上,諸同儕跟隨貴氣的師長振臂疾呼文化的存續,我卻生生眼見官式廟堂外黎庶鄉情的寸斷。二十年國與君,極力維護的究竟是什麼傳統?為什麼倦看呼召,我虛長橫眉兩條?

The most ritual generation has faded away. The belief of respecting our ancestry, which has been taught for centuries in our history, assures me of no confidence that it will stay intact in my generation and the next. High above the altar of the ivory tower, my peers are crazy excited following the dear elites in clamor for perpetuating our culture, whereas I witness the vivid break in home-bound ties out in the wild far from eloquence. What tradition on earth has our nation, in these decades, defended and fought for? Why have I been so tired of the appeals and filled with aloofness?

在深秋的葬禮上,聽陰陽先生搖著招魂幡蒼涼一嘯,搭起金橋牽亡一躍,幾十載的血呀汗啊、數千年的痛呀恨啊,卻一時間全逼心口、淚如雨下。故鄉的魂魄幽憤著飄蕩在丘間陵間,它世世嘶吼出的悲聲,歷歷充斥著人生的苦楚,何處見金科玉律、何處是恢弘與典雅?

At the late-autumn funeral, when the old ritual master waved the spiritual flag in a desolate moan calling for the return of the one who had died on a foreign land, acrobatically built up the Gold Bridge on stacked benches, and invited the spirit for a leap home, years of blood and sweat and eternity of misery and remorse all together seethed in, rushing into tears pelting down. The soul of hometown hovers over the hills and mountains, bitter and sour, and wails in a voice bearing generations of pains and sorrow. In this hail of howls flesh and blood, where is the declamatory elitist call? And again, where is the grandiose ideology?